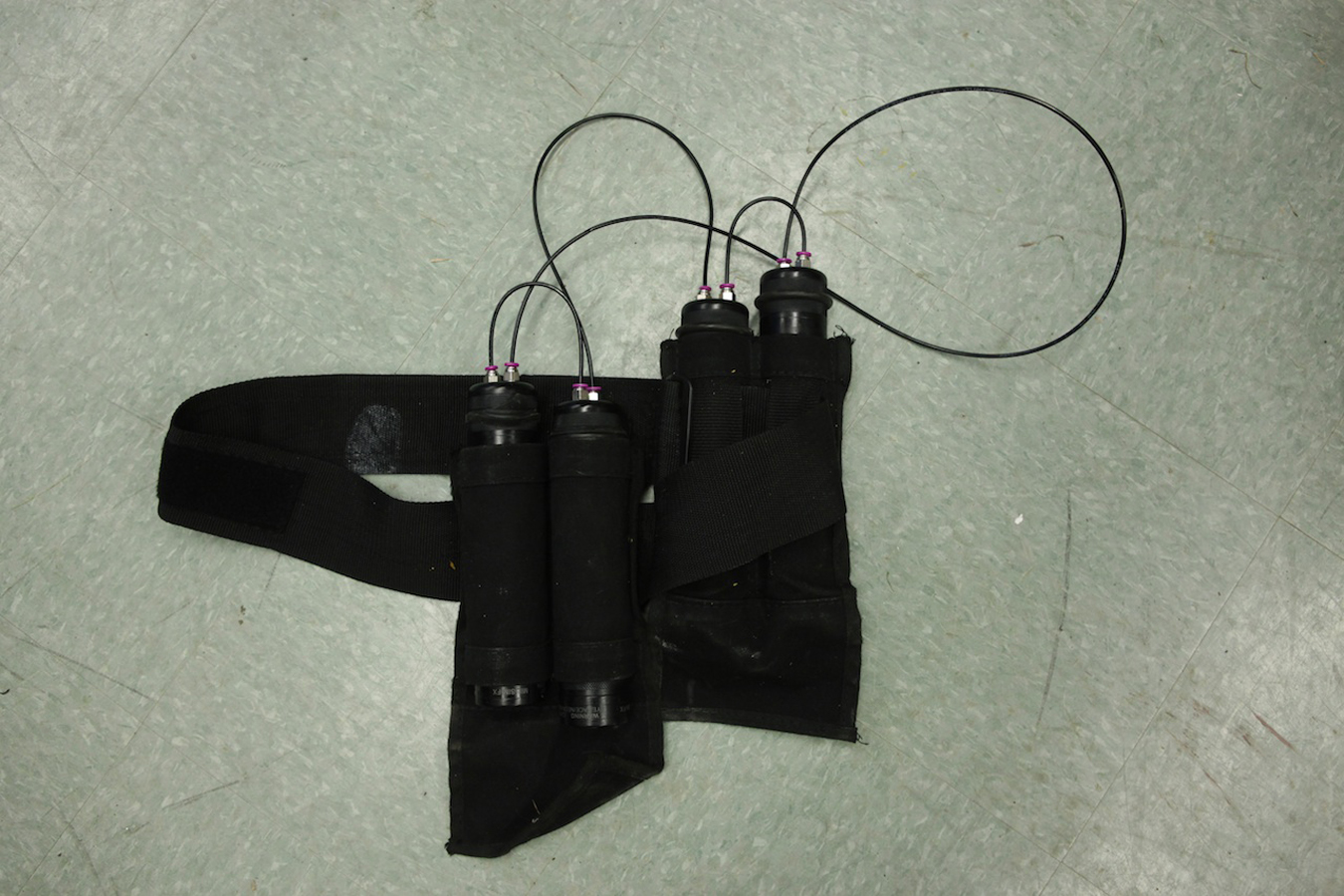

My participation in the Canadian Forces Artist Program included 6 weeks of specialized training for deployment to hazardous environments and UN military observer/peacekeeping service, followed by a month-long tour of Sudan embedded with the Canadian Forces as an Official Guest of the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS). Both pre-deployment training and deployment were intense, dislocating and disorienting. In hindsight, the utility of the training was its very disorientation –one prepares best for the indescribable who does not pretend to a capacity or readiness to understand. I submitted to the CFAP experience to learn about protection, trauma and post trauma, and gain new perspectives on colonial narratives. As an artist of the African Diaspora, I have been particularly focused on making sense of the experience through the privilege of a Canadian filter within the echoes of my family history – colonials and Afro-Caribbeans of the transatlantic slave trade / refugees of Nazi Germany.

Before my travel to Sudan, I would wish to make sense of the concept global citizen, of world events, of intervention, of beauty and the violent order it interrupted. From the safety of here, of our skins, our institutions, the shoulders of our dead, I could imagine understanding, and even grope for explanations. If before I believed the world was amenable to being explained, to making sense, it was from my comfortable seat in the theatre of our institutions, resources, entitlements and entertainments. It is a belief arising from walled-off, supervised and patrolled ignorance. It is a belief sustained by the very agents of information that bring us news of elsewhere –network, wire and page.

As I am informed about the world and its unfortunates from the privileges of safety, so I am distanced from them. The impossibility of language, and its ornaments –photos, reports, documentaries, clips, to convey experience so far beyond its own context is unimaginable. I went to Sudan to attenuate my elegant defences, and to reach a little better through that wall, to touch a small part of the body of my motherland. I breathed her air, I let her eyes see me and looked into her own, and I returned. after Africa is the story of that difficult gift, and the vision that pursues me because of it.

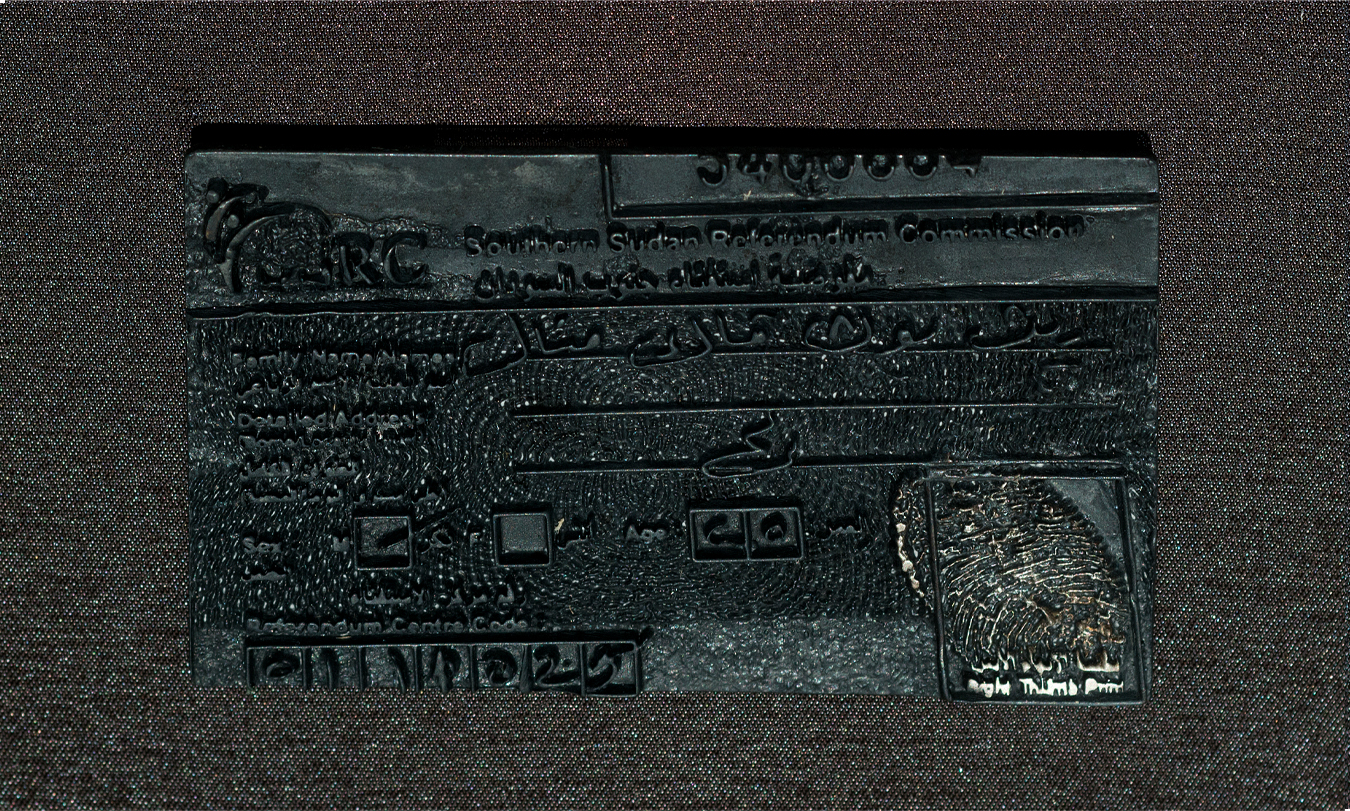

(With the UN in Sudan I met real people –pre-victims, would-be bodies –lives about to be lost to violent aggression, just weeks before the international press would deliver news of their murderous demise. I visited a hospital that smelled like festering wounds. I chatted with a man whose both legs were penetrated by the same bullet. I saw a boy child whose whole body was burnt along with his sleeping mat and mud hut. I met militarized men who, mere days earlier, had engaged battle at Kaldak that saw 254 dead, over 500 wounded, and an estimated 1500 surviving villagers displaced with nothing left to do. Those proud armed men still had the self-possession to shake my hand, smile at me –compliment my endeavor to understand, my bravery for setting foot, and the helpfulness of my good looks. At the war I tasted the odor of death in 52 degree heat. I heard the flies feasting and the vultures circling –staking territory over their scrap.

Now, motivated to remember, to disallow the flight of memory, I comb the internet looking for bodies of evidence.)